HAPTIC VISUALITY OF JEWELLERY. PSEUDOMAGIC AS ARTISTIC RESEARCH METHOD

Darja Popolitova

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

Text

The text is a draft for the methodological chapter of Darja Popolitova’s doctoral dissertation. Stipulations and conclusions may differ in the final text, the defense of which is scheduled for December 2024.

Let’s talk about how gallery visitors experience the audiovisual images of jewelry on screens. What are the qualities of such images, and what effects do these qualities have on viewers?

To answer this question, I will rely on my artistic methodology, representing my approaches as transparently as possible so that other artists may be able to relate to the subject. I believe that all artists share a commonality regardless of our respective disciplines or mediums. This commonality ispraxis, the process of putting theoretical knowledge into practice through the creation of art.

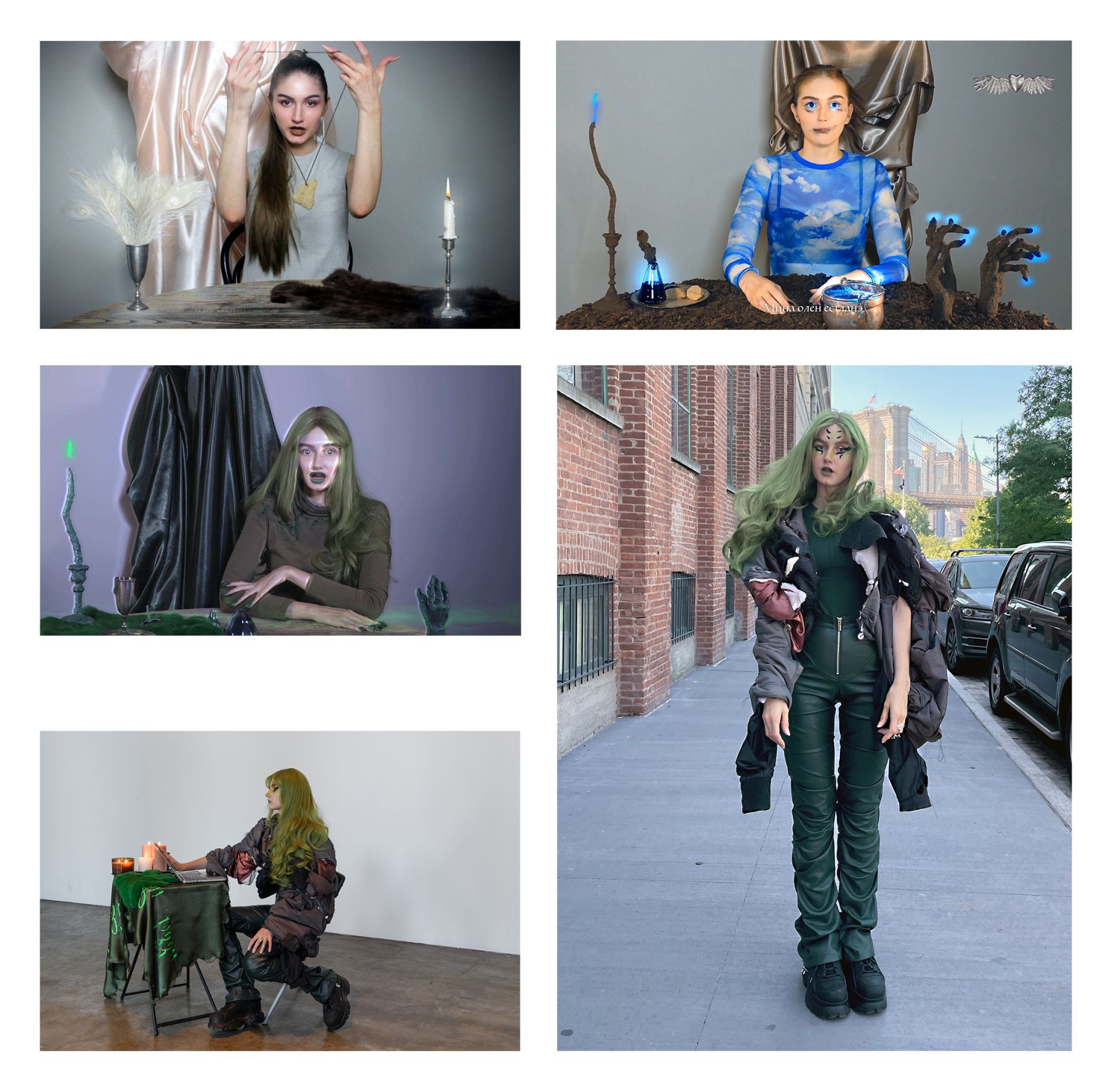

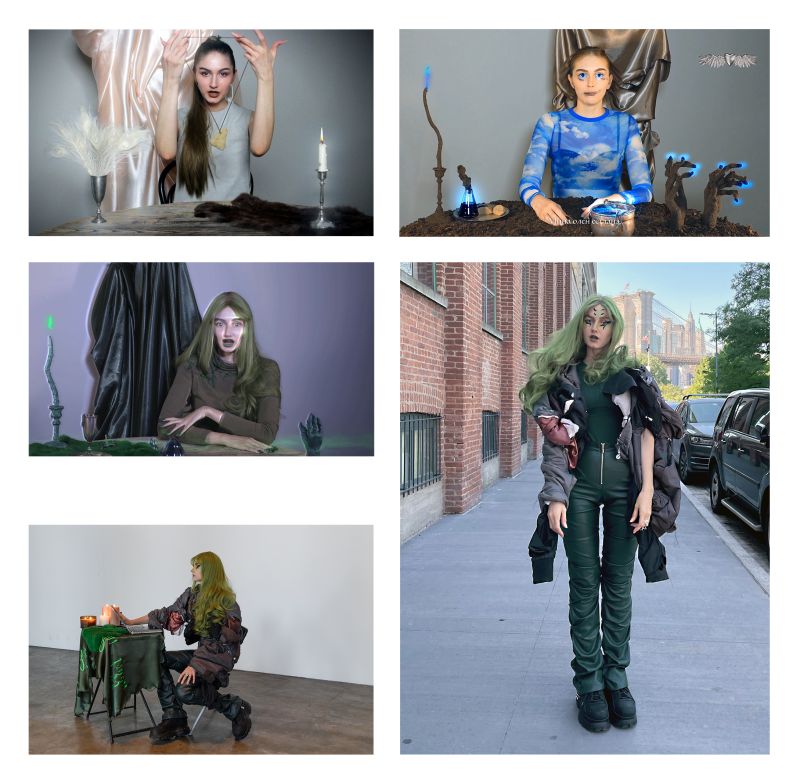

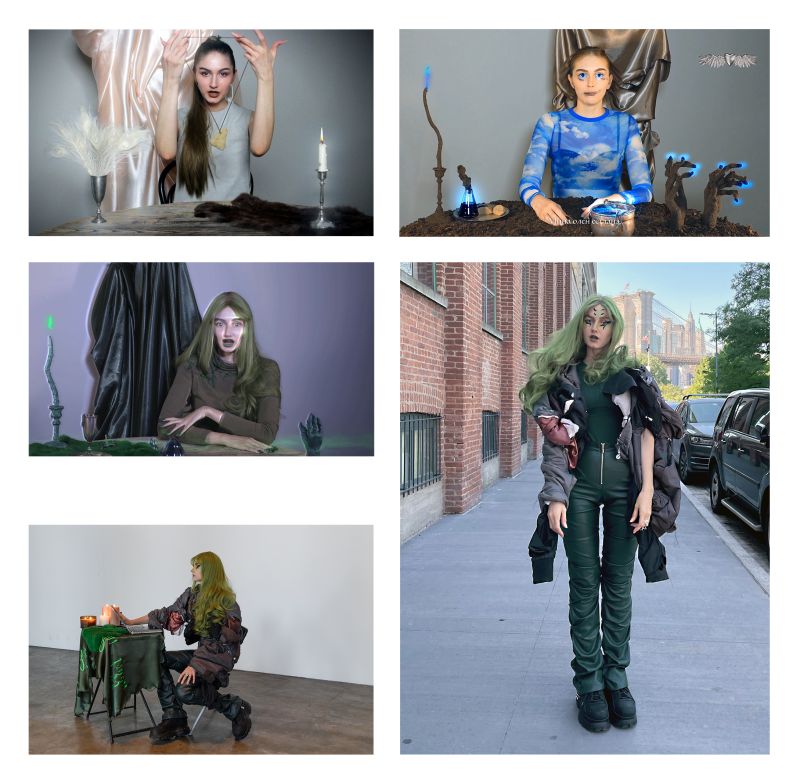

SERAPHITA

As a contemporary jewelry artist, I inhabit a gray area, where jewelry is a tangible, wearable (but not always) artifact but also a self-reflective, artistic practice. This practice involves the use of diverse materials, technologies, themes, and mediums to shape a field defined by ambiguous identities and multidisciplinarity. The Jewelry Witch Seraphita, a fictional character from my solo exhibitions, helps me to widen the scope of jewelry’s usual function. Seraphita is not only a part of my artistic practice but also of my PhD research at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

Seraphita is accompanied by Pseudomagic, a theme, format, or appearance informed by mainstream-cultural ideas about magic. Pseudomagic can be found in internet culture; for example, in the videos of (often female) YouTube vloggers who dedicate their channels to mystical narratives and rituals. In a 2019 article for Rhizome titled “Why Youtubers See Ghosts,” Sofya Aleynikova explains that the paranormal vlog has gained traction in recent years, becoming a popular and peculiar genre in which primarily femme-presenting, cosmetics-wearing characters share ghostly stories about their inspirited dogs or the disappearance of their clothes from their closet. The composition of these videos usually involves a front-facing narrator in portrait mode.

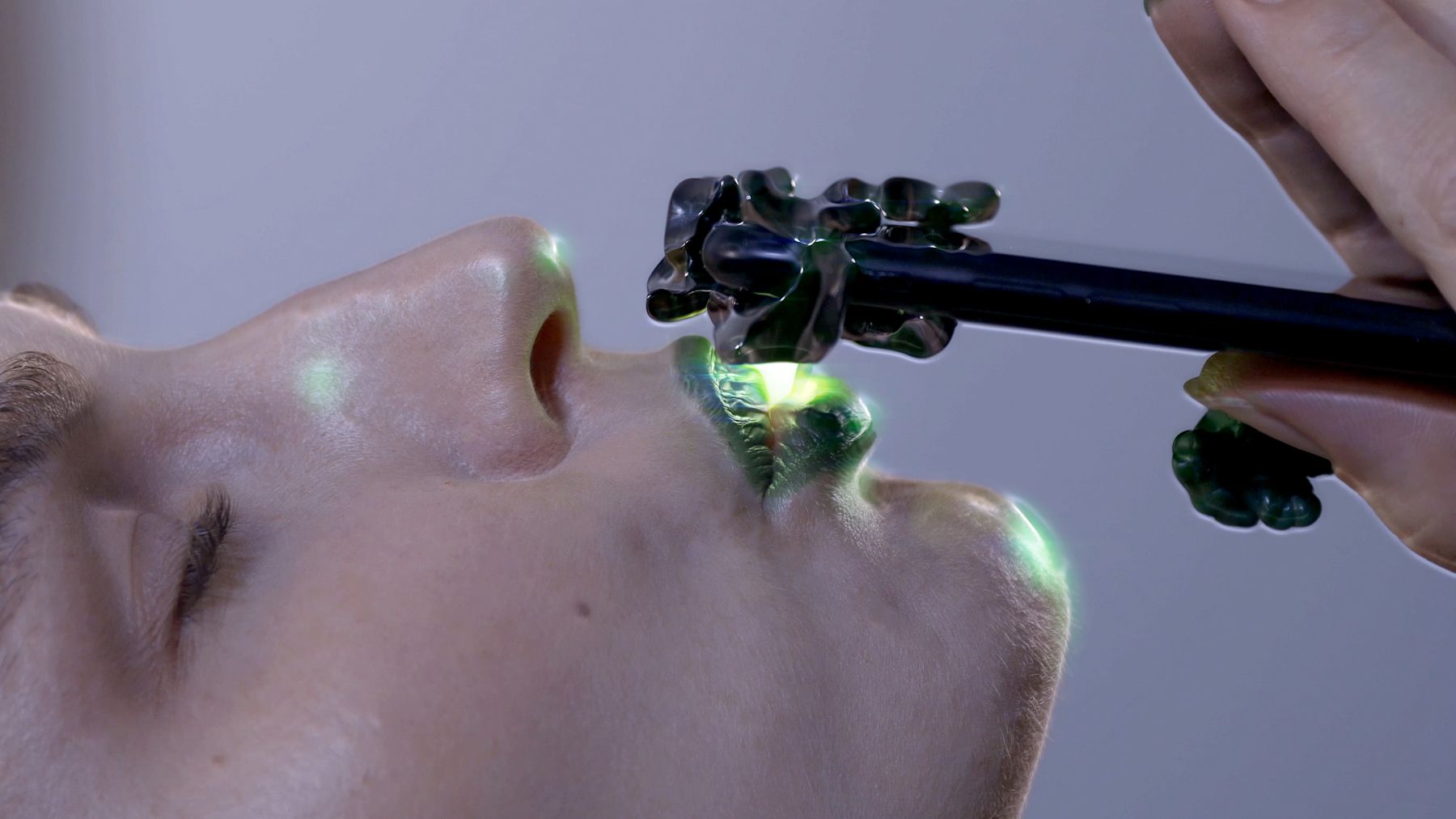

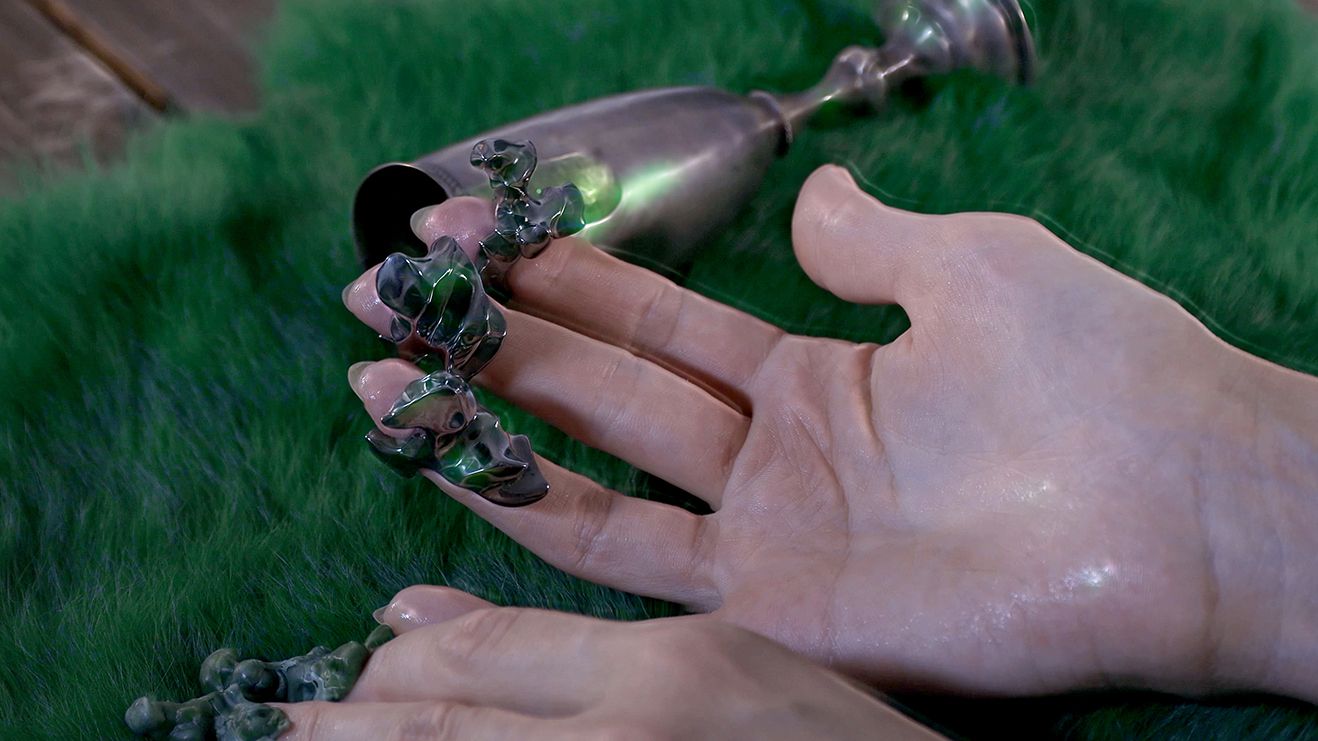

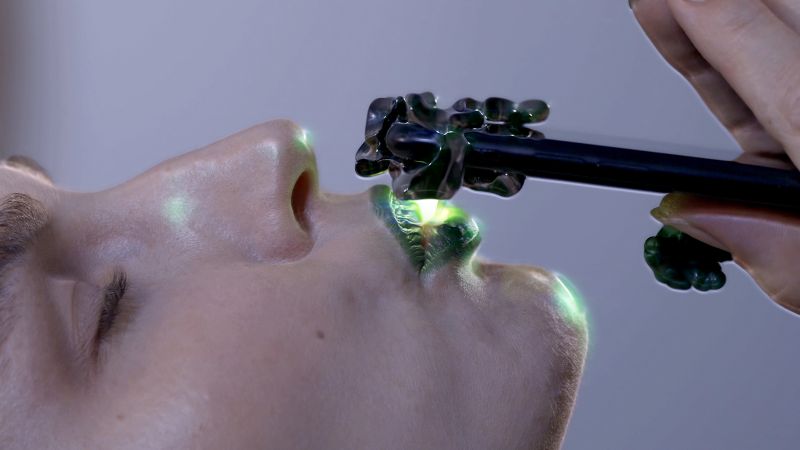

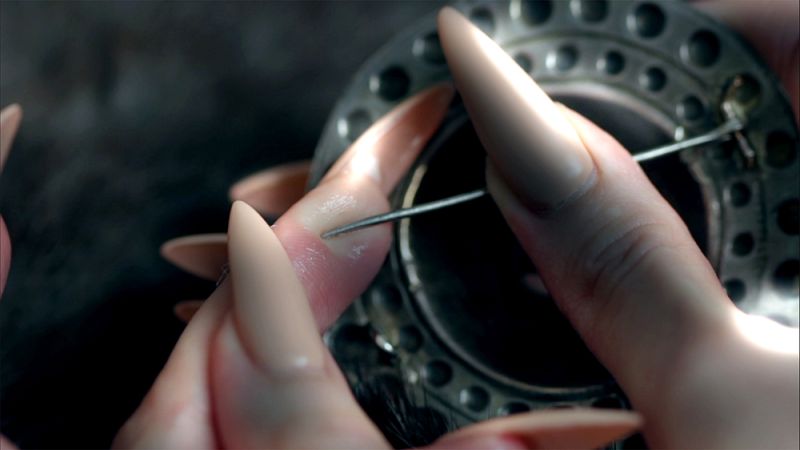

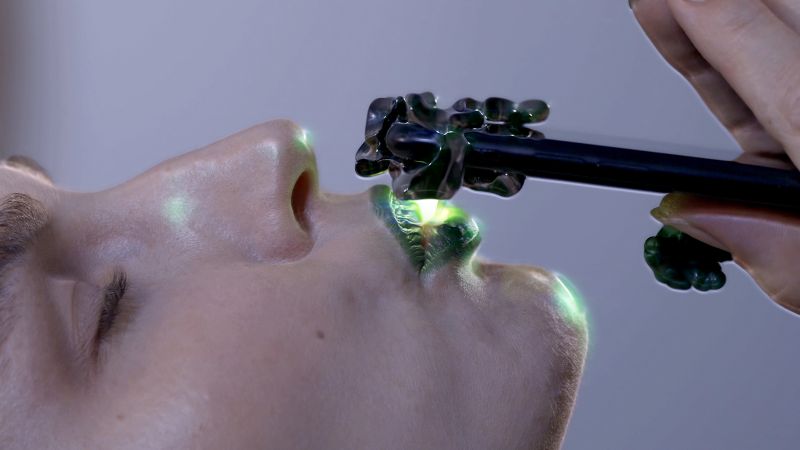

Pseudomagic can be understood as the thematic and stylistic power of Audiovisual Jewelry. This power is perceived in the videos, in which Seraphita performs bodily actions with pieces of jewelry as if they were ceremonial implements. As in a YouTube tutorial for a ritual, the jewelry is shown as a speculative instrument.

Seraphita’s purpose is to facilitate the study of Haptic Visuality, a term popularized by new-media theorist Laura U. Marks that refers to the multisensory way that we experience visual phenomena like audiovisual images.1

Haptic Visuality is a perceptual concept that transcends traditional visual engagement by incorporating the sense of touch and other bodily sensations into the act of seeing. Originating from film phenomenologists such as Vivian Sobchack and Laura U. Marks, it represents an embodied approach to visual experience that goes beyond the mere observation of images and delves into a multisensory realm.2

The quality of an image is part of its Haptic Visuality. For example, low resolution, blur, close-ups of textured objects, or damage such as scratches on film and digital glitches can all affect a person’s experience of a video’s hapticity.3

Often, when I the study Haptic Visuality of Jewelry, I become dissatisfied with the limits of visuality, because I want to localize it on and under the epidermis. I create Audiovisual Jewelry to be experienced through the body, and I gain insights from the public—the (usually) silent observers—by asking them to describe how they experience the convergence of Haptic Visuality and Jewelry in my work.

From this perspective, magic is a phenomenon in which people see the power in objects—powers that can alter their lives and bodies. These objects can be sacred artifacts not meant to be touched, but which are believed by people to heal.

I have thus chosen the context of Pseudomagic, where Haptic Visuality is the norm—it tickles the body without any contact between the skin and object. Even if a person does not believe in video rituals, they are aware of the Hapticvisual rules present in Pseudomagic.

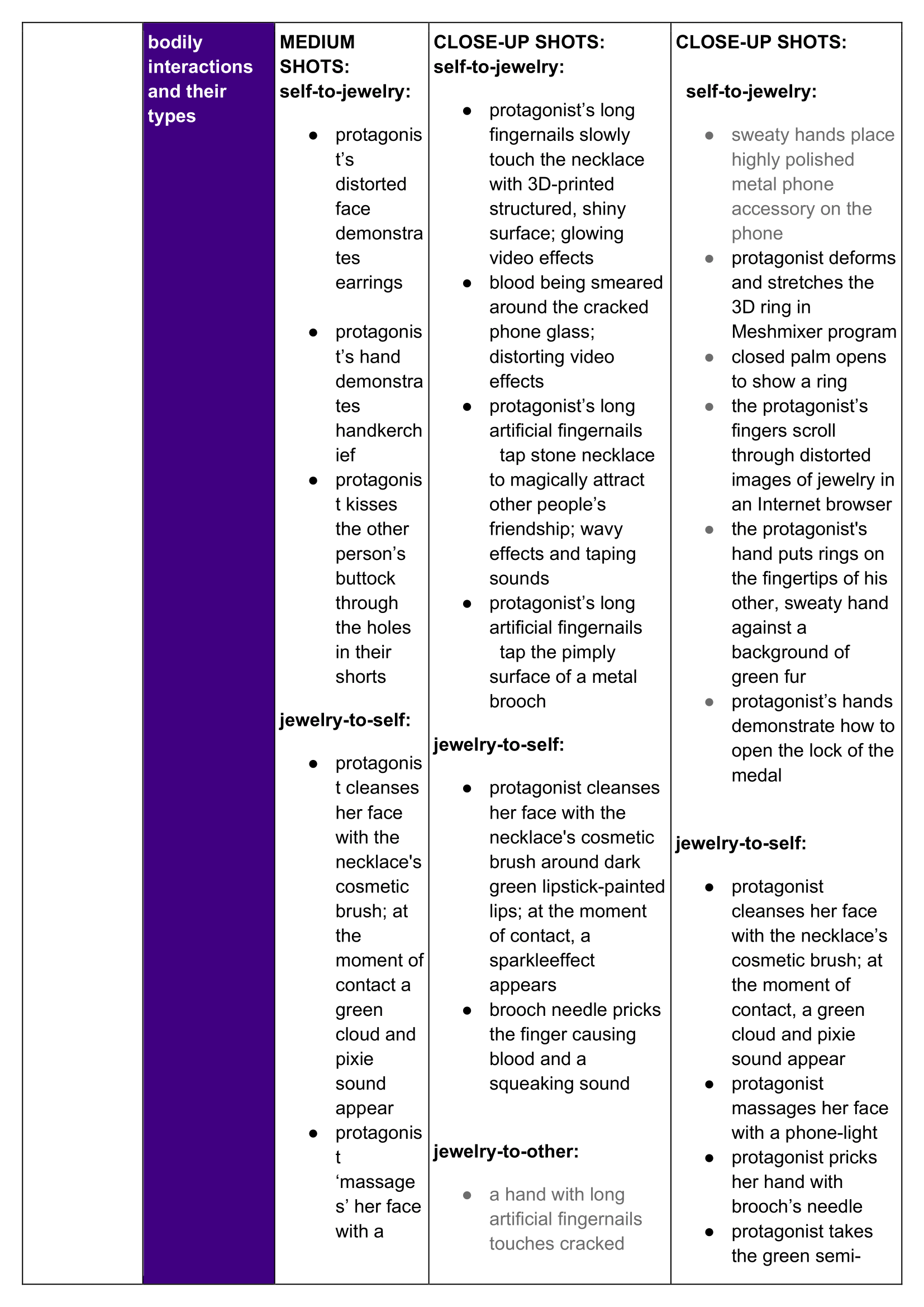

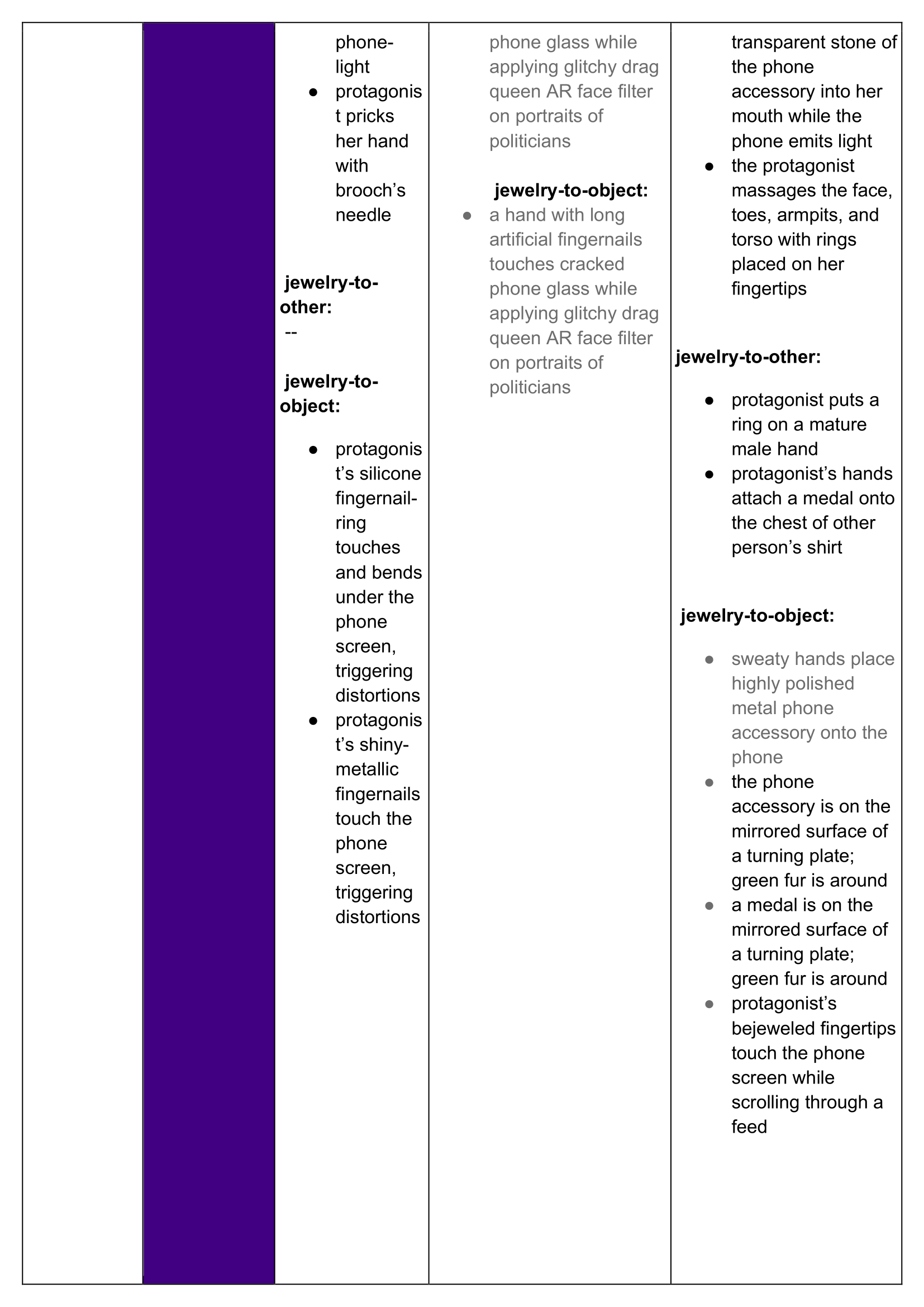

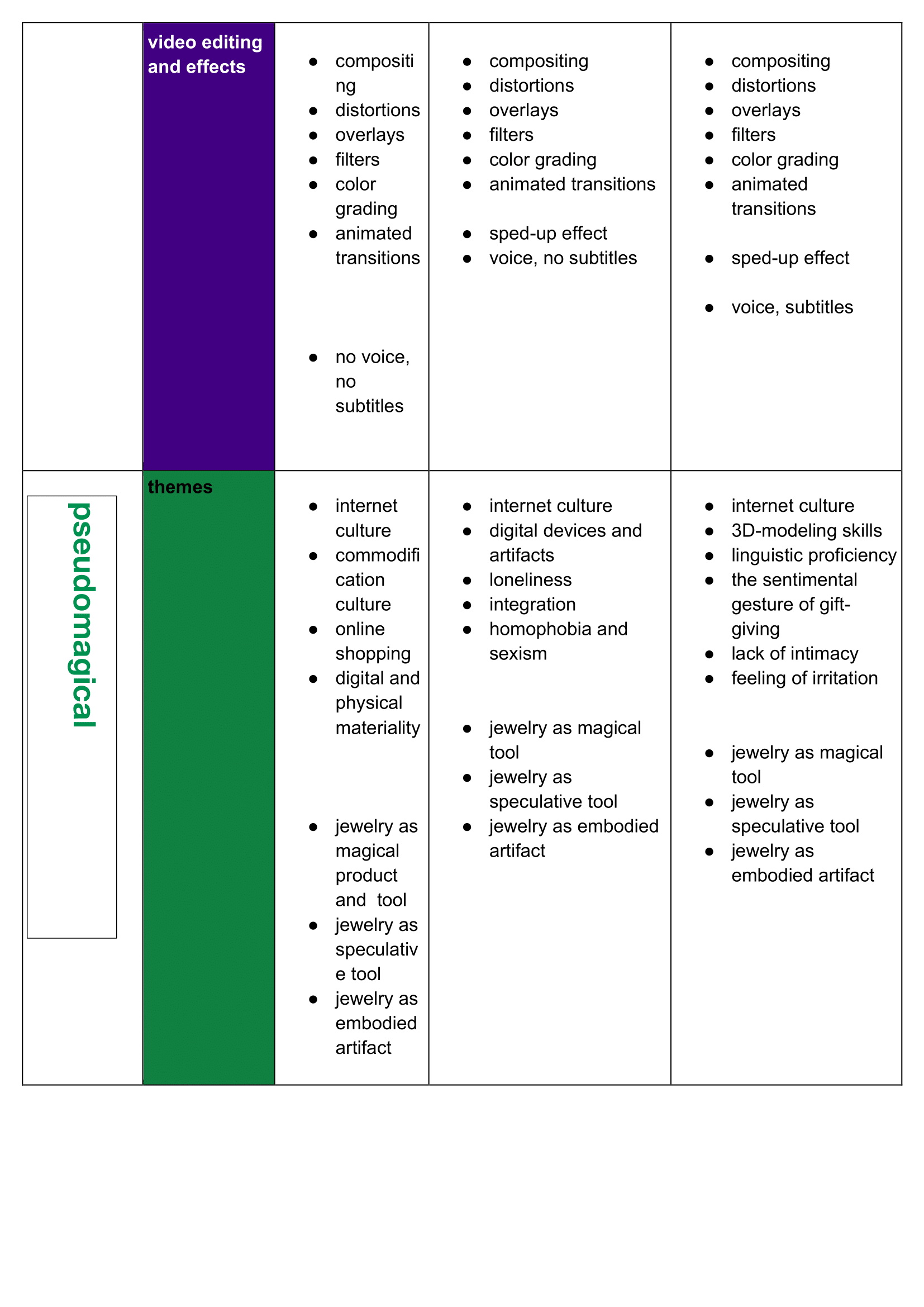

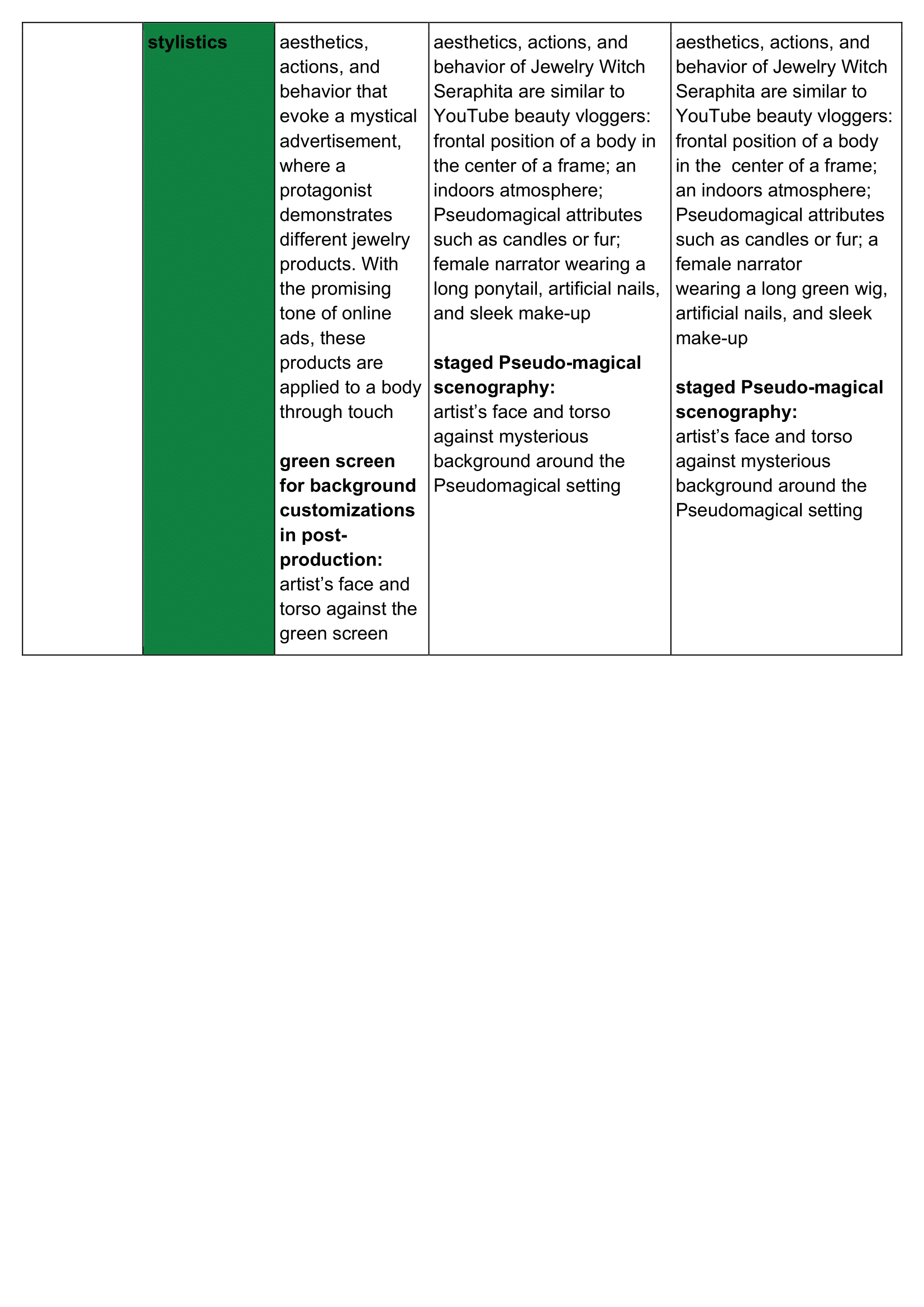

Seraphita incorporates widely accepted cultural ideas about magic, which together embody the compound-element of my research, Pseudomagic. Seraphita is born of the need to incorporate a feedback mechanism into my exhibitions, to create a situation in which the visitor, the work of art (in this case, Audiovisual Jewelry), and the artist all find themselves in the presence of one another. In the below section, I illustrate this tripartite relationship with tables.

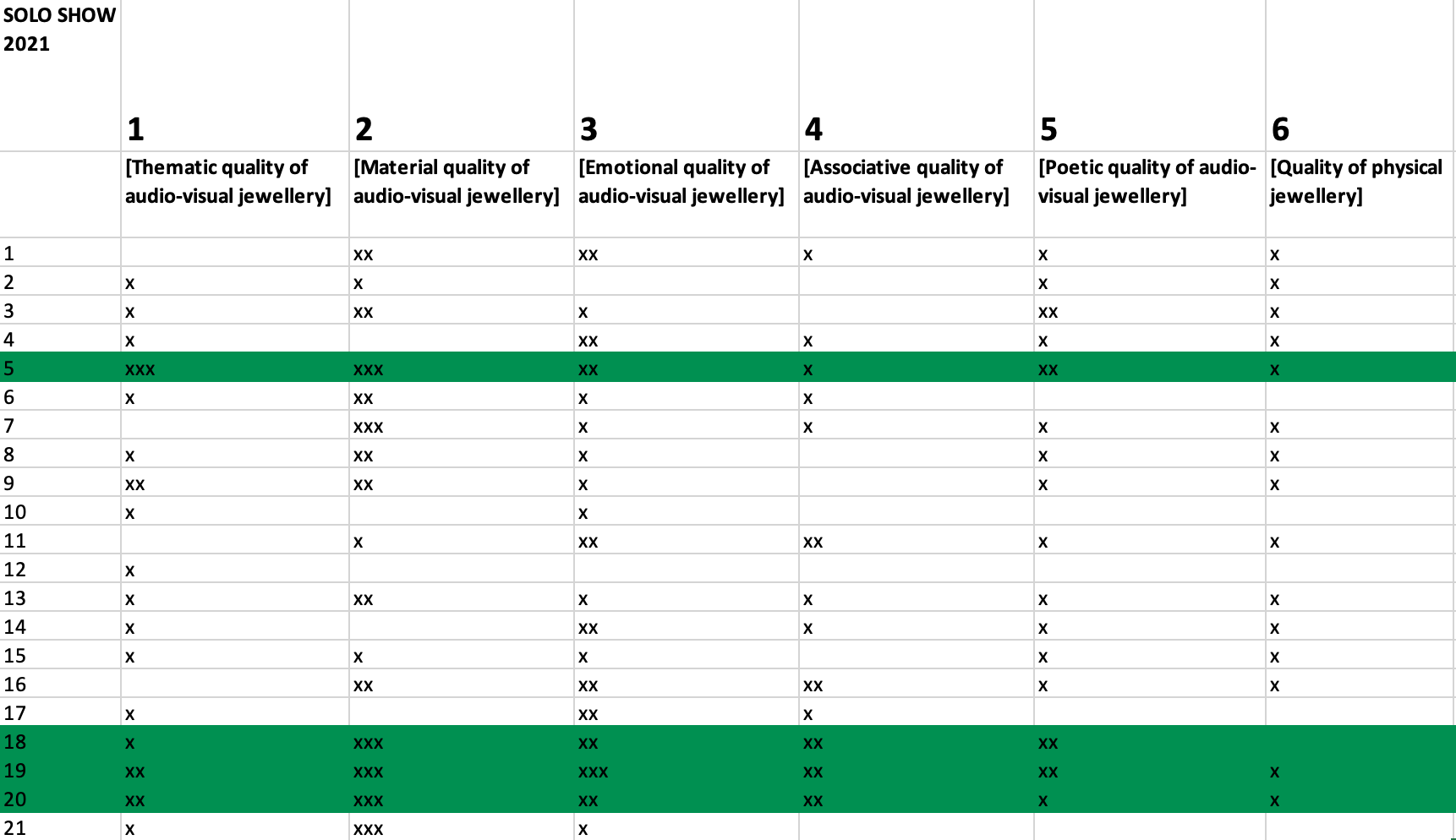

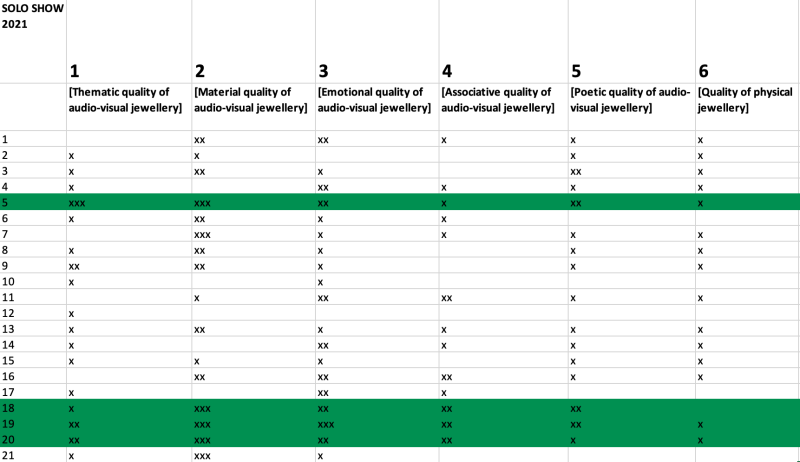

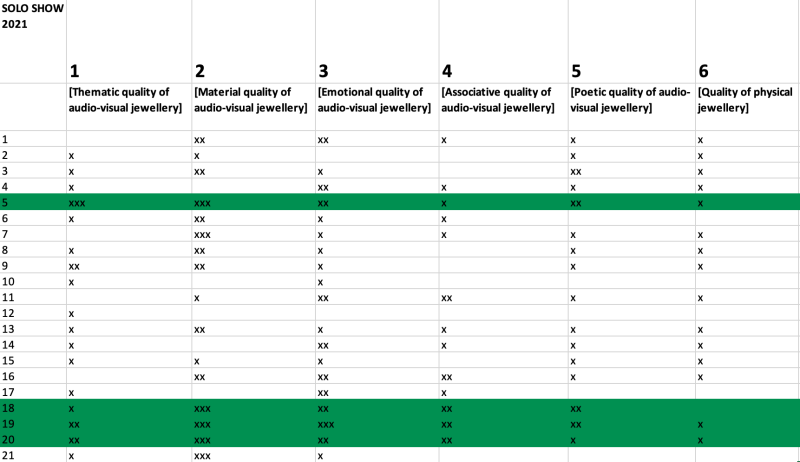

SOLO SHOWS

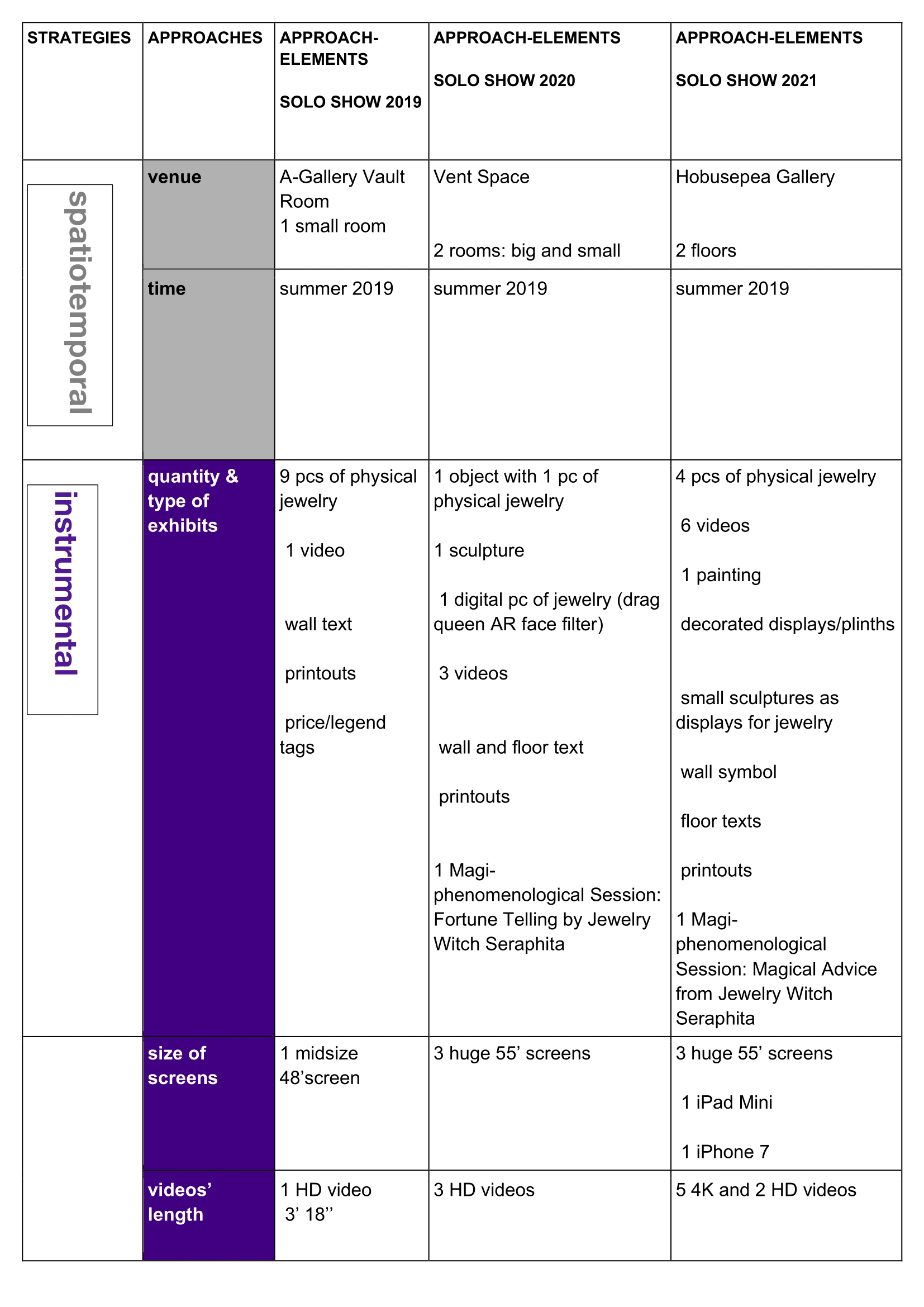

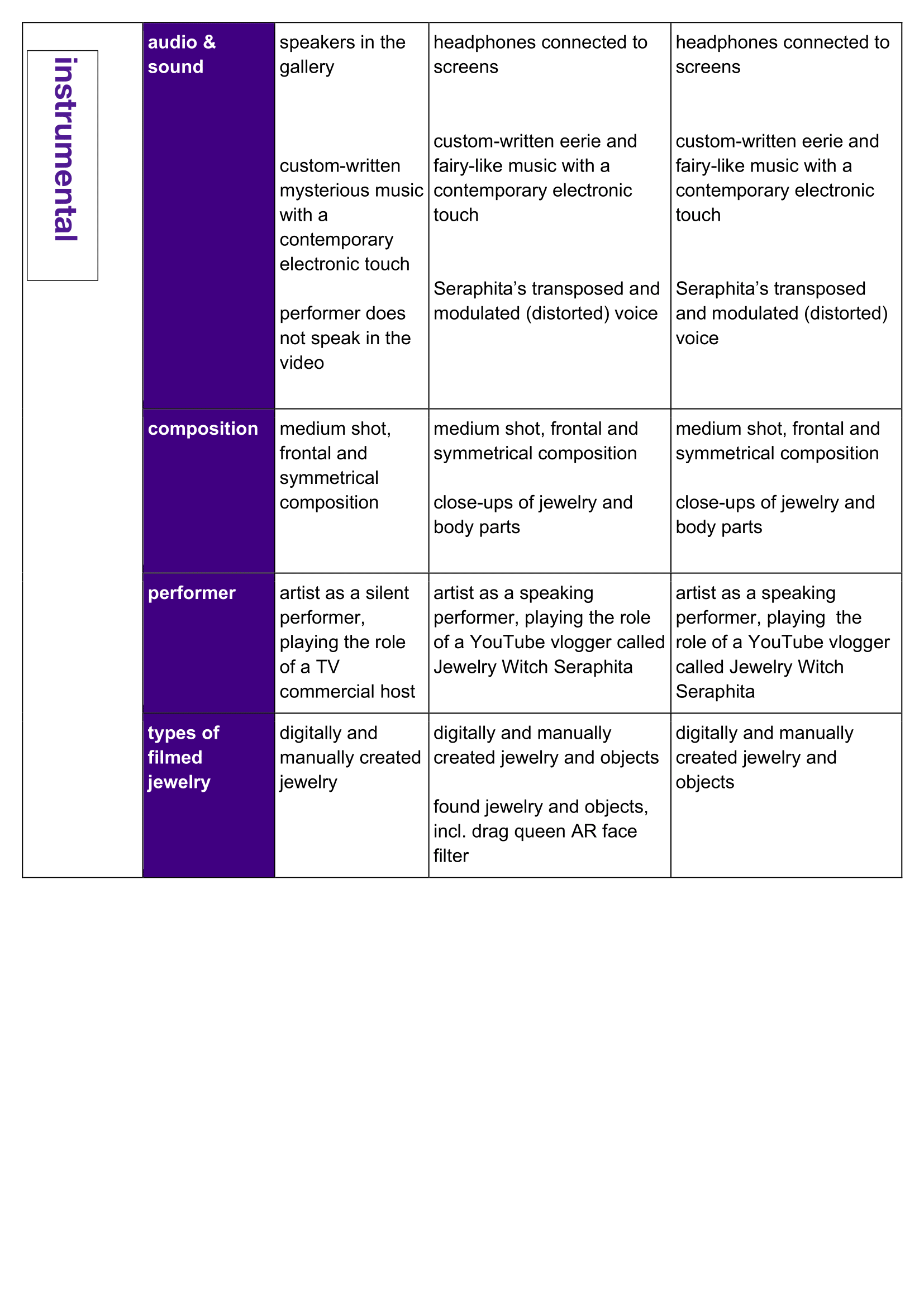

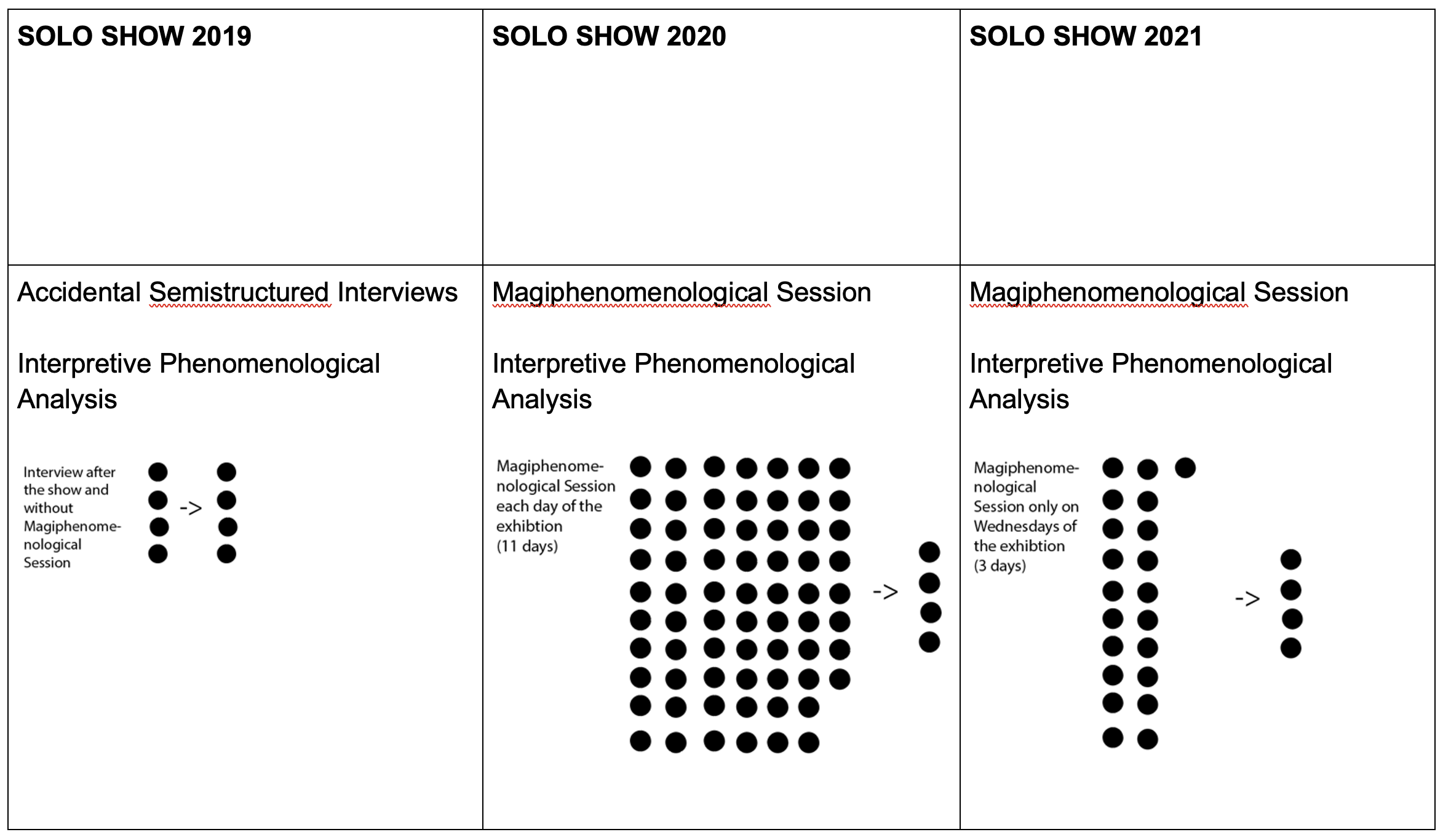

I created three solo shows where I tested how people experience Audiovisual Jewelry. For each of the shows, I designed the artistic research metaphorically, drawing together seemingly unrelated approaches to help the audience make sense of the complex dynamic.4

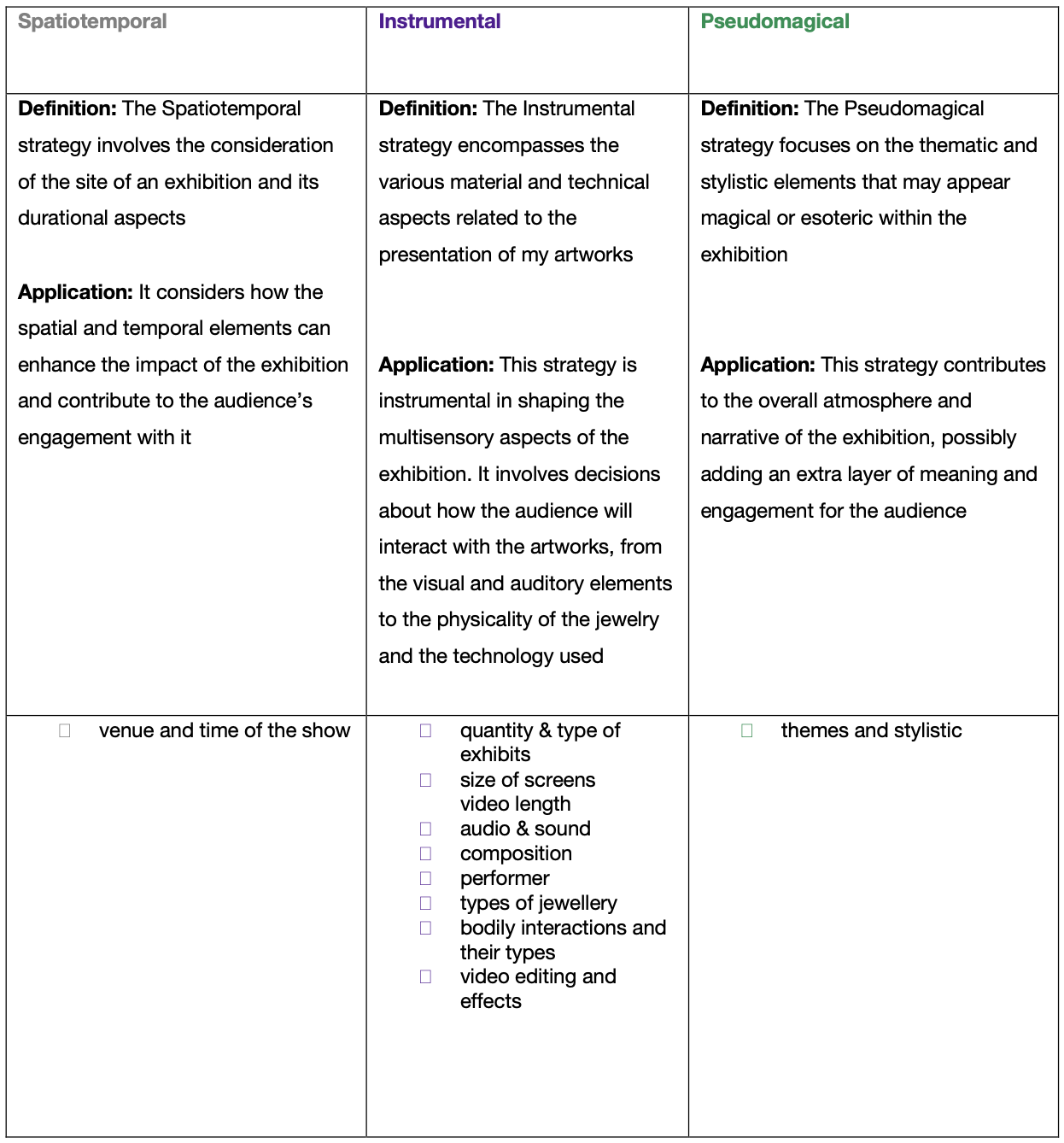

In order to address Haptic Visuality while working on jewelry, videos, and other artworks, I employ three different strategies:

Spatiotemporal

Instrumental

Pseudomagical

In the table below, I offer an example of the Metaphorical Structure of each of the three shows, in which the three approaches are applied toward the process of creating and exhibiting Audiovisual Jewelry.

DATA COLLECTION & ANALYSIS

I used two empirical methods to collect and analyze the data on how visitors were experiencing this kind of video. I applied these methods in the following sequence.

Magiphenomenological Session is a dialogue-based feedback system with dramaturgical elements that is used in the exhibition space. It is kind of a parody of an interview — the method that falls inside the scope of phenomenology, but also deviates from its protocols by developing a stylized and performative context in which the audience is being asked questions and interacted with by the Jewelry Witch Seraphita.

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis is a qualitative research methodology, developed by Jonathan Smith and his colleagues, that has become a widely used method for studying subjective experiences.

5I use it for data analysis to understand individuals’ lived experiences of the exhibitions.

SELECTION OF PARTICIPANTS

The following two methods of selection were applied to each show:

Convenience Sampling: a method in which subjects are selected due to their accessibility and proximity to the researcher.

Purposive Sampling: a selection method that aims to gather information from individuals whose articulations possess characteristics specific to my research objectives (codes). This process involves the extraction of “high-quality” samples from the data set.

The following table indicates which selection methods were used for each show, how many people were interviewed, audio recordings transcribed, and transcripts analyzed.

During my solo show in 2019, it was still unclear to me how best to apply the qualitative methods described above. Therefore, the selection of respondents was the least organized: four people were interviewed at a party, in the lobby, in a cafe, and the very number was un-filtered/ without a Purposive Sampling since the number was anyway small.

With my solo show in 2020, came an added a degree of confidence: In fact, I was so confident that I decided to interview every possible subject, which ultimately took a great toll on my mental and physical health. Every single day, I sat at the exhibition. I recorded interviews with 68 people, transcribed all the recordings, applied Purposive Sampling, and selected four samples for further analysis.

By the time of mysolo show in 2023, I had let off the steam of ambition and was more restrained and methodical in my approach. I was present in the gallery only on Wednesdays and interviewed the optimal number of 21 people. Then, using Purposive Sampling, I chose four interviews to analyze.

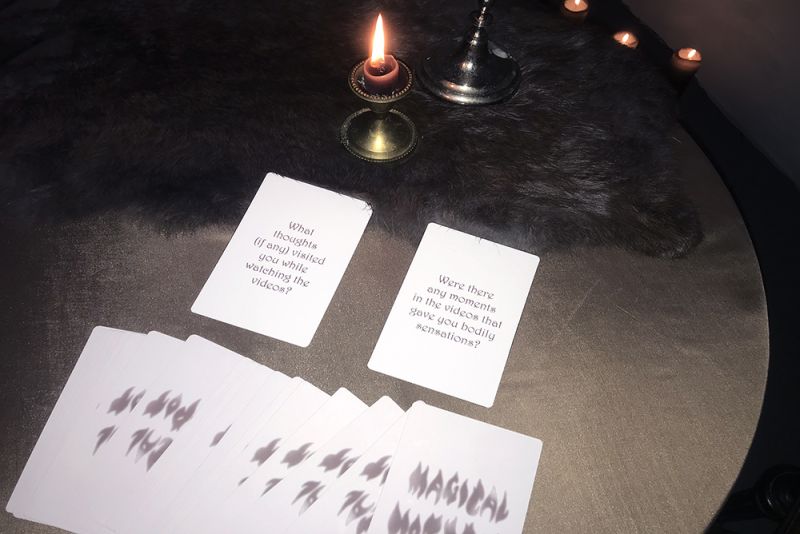

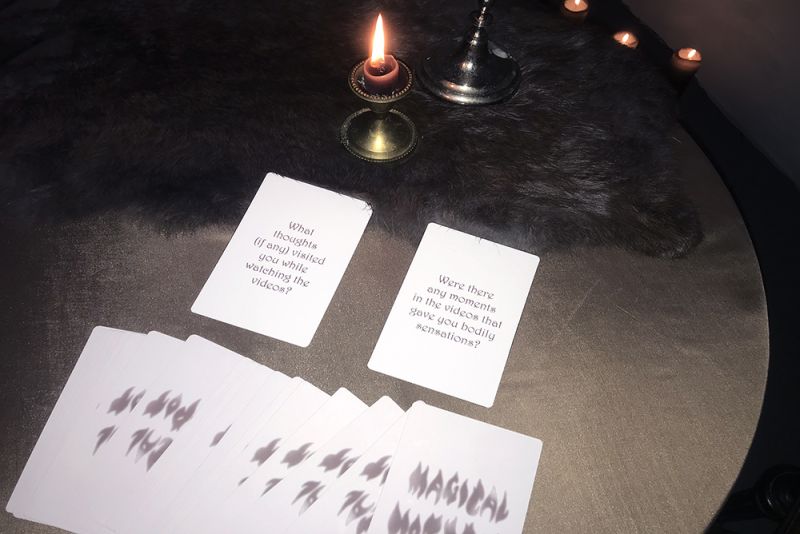

MAGIPHENOMENOLOGICAL SESSION

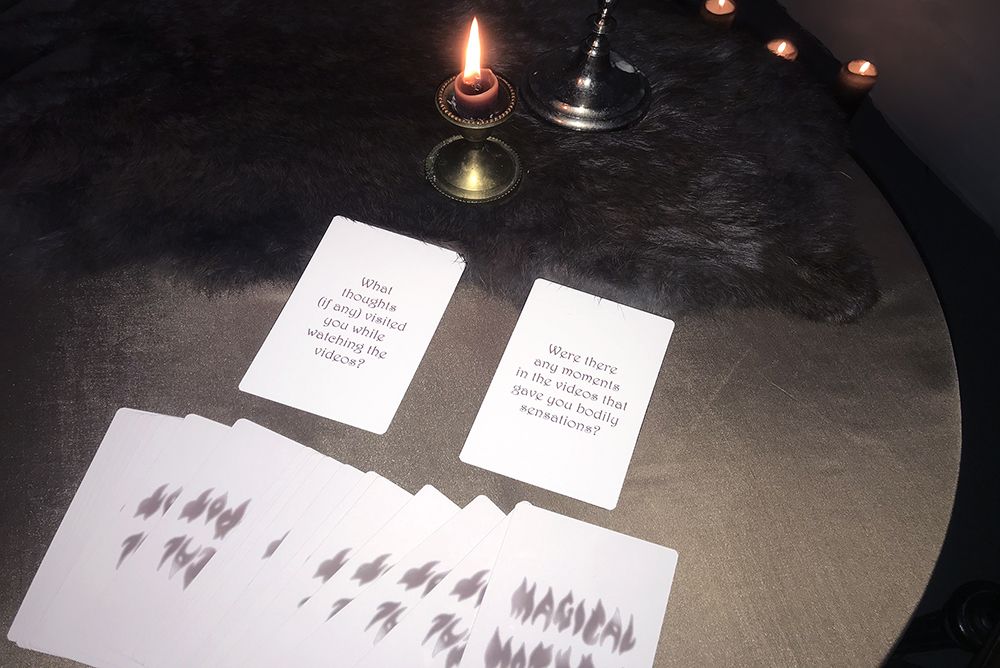

In the Magiphenomenological Sessions, the openness and interest of the visitors, their free time, as well as the availability of the chair (it may be occupied by another visitor) are the main variables at play.

Thus, Seraphita sits in a small dark room with a table and two chairs. She is surrounded by candles, the setting is intimate: muffled light, satiny tablecloth, playing cards, fur. In the rest of the gallery, there is the exhibition, with physical jewelry and videos about it.

The interview questions are printed on playing cards and handed out to visitors as part of a “fortune telling” that they have agreed to participate in.

Phenomenologist Laura U. Marks reminds us not to look for the haptic perception in rationalization or preconceived ideas or theories, so I am not interested in the analysis of cognitive acts, but the phenomenon of Haptic Visuality. Therefore, I ask the following questions, which I have constructed in such a way as to reduce the likelihood of a respondent falling into excessive intellectualization:

How was it like: to feel, to watch, and to experience the jewelry in the videos?

What was the jewelry like in the video?

At the end of the session, after the reflections, I treat the respondent to an improvised “fortune telling,” during which I speculate on their destiny.

ANALYSIS OF MAGIPHENOMEOLOGICAL SESSIONS

The Magiphenomenological Sessions provided a lot of data on the personal experiences of the exhibition visitors. While listening to the audio recordings, I identified the codes (or categories) that I used to organize the collected data. These codes allow me to systematically examine the transcripts for insights about the Haptic Visuality of jewelry. The coding process involves assigning labels to segments of the transcripts that address the research’s points of interest.

It turns out that if I apply the Spatiotemporal, Instrumental, and Pseudomagical approaches toward the Audiovisual Jewelry and ask visitors to reflect on them during the Magiphenomenological Sessions, some recurring characteristics can be identified. Thus, by analyzing the audio recordings of the Magiphenomenological Sessions with Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis, I isolated five categories of characteristics of Audiovisual Jewelry:

Thematic

Material

Emotional

Associative

Poetic

These five types of qualities are experienced Hapticvisually, meaning that visitors feel them on both the surface and the inside of their bodies. In this regard, visitors may:

notice the Thematic quality: the underlying themes, concepts, and ideas that are conveyed by the presentation of Audiovisual Jewelry. They identify the philosophical concepts and cultural commentaries within it, and, surprisingly, their observations are sensorially specific

“The idea of the video — how the sharpness, humor and irony work together — was spicy and made me feel excited.”

Idea > Spicy = Taste Reference

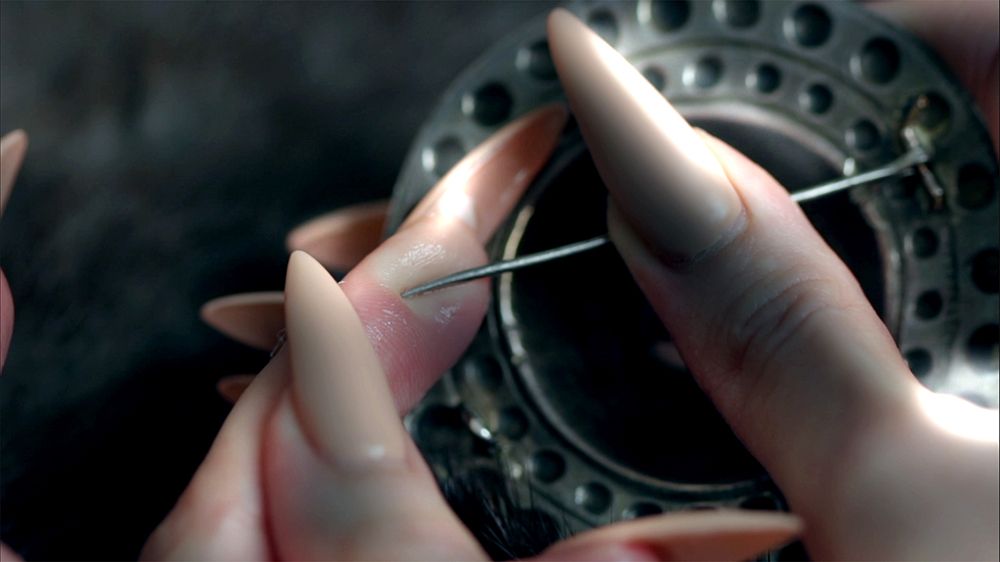

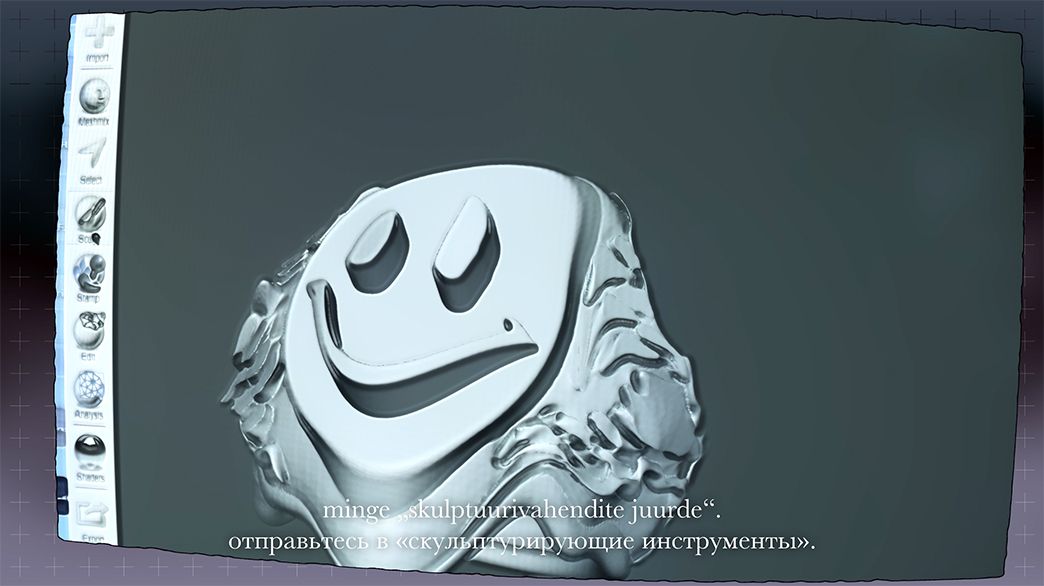

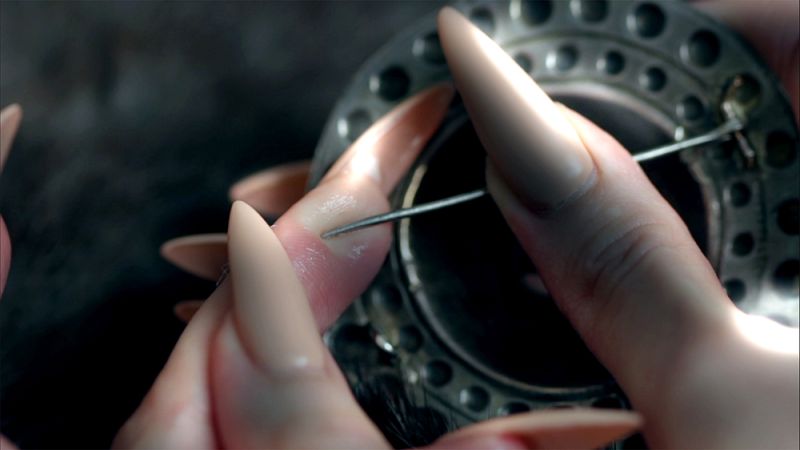

feel the Material quality: the textures, materials, temperature, sound—the raw-substantial attributes that contribute to the visual, tactile, auditory, and olfactory aspects of the Audiovisual Jewelry

“The jewelry in the video felt clean and sharp…”

“I noticed the distortion and glitch when the necklace’s thread was knotted up.”

Necklace > Distorted & Glitchy = Material Reference

experience the Emotional quality: the capacity of Audiovisual Jewelry to convey emotional content, and allowing it to connect with them on a personal level

"I felt scared when a brooch’s needle pricked the finger.”

Brooch Needle > Scared = Emotional Reference

perceive the Associative quality: the ability of Audiovisual Jewelry to elicit connections, associations by relating it to their own experiences, memories, or cultural references

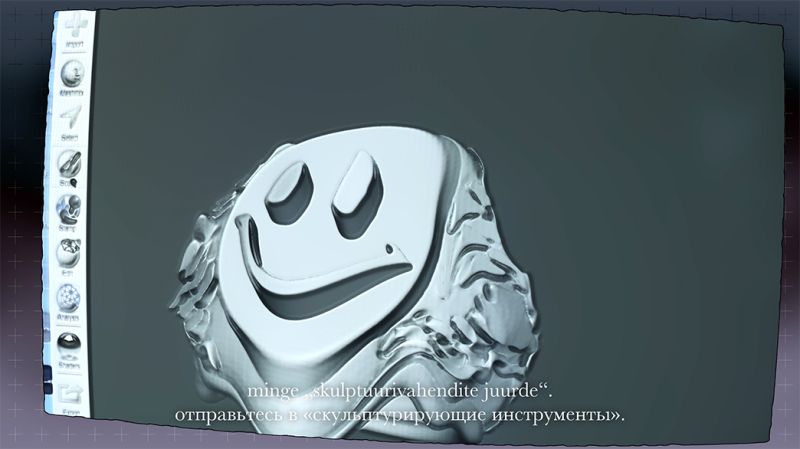

“When it comes to watching the silicone rings, the sculpture-lesson comes to mind — the feeling of what it is like to touch the silicone.”

Sculpture Lesson > Distant Event > Associative Reference

observe the Poetic quality: the ability of Audiovisual Jewelry to evoke a sense of beauty that is akin to the qualities found in poetry

“The jewelry felt a bit eerie, but hopeful. All of the jewelry offered solutions and gave hope, in such a happy, humorous, and healthy way.”

Jewelry > Eerie = Expressive, Aesthetically Charged Language

CONCLUSION

While I cannot give final conclusions since the full analysis is not yet complete, in my search for the answers, I have come to use the following methods:

Magiphenomenological Sessions

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

I designed the feedback mechanism of the Magiphenomenological Session to collect data on how individuals expeerience the Audiovisual Jewelry in the exhibition space; spend time next to the videos, their gaze wandering over the details, textures, and forms; experience ranges of emotions; propose personal interpretations; search for symbolism; and find expressive language to reflect on what they have seen.

With the help of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis, I make detailed notes and reflect on my creative process and concepts, which helps me make decisions for future shows.

Through different tests experimenting with the creation and exhibition of Audiovisual Jewelry, I began to understand how Hapticvisual qualities—such as Thematic, Material, Emotional, Associative, Poetic—work in the context of Spatiotemporal, Instrumental, and Pseudomagical approaches.

In addition, I have developed a guide for artists who would like to apply Haptic Visuality toward Audiovisual Jewelry:

Look for tactile qualities when searching for material for jewelry. These could be prickly spikes, brushes, or slimy, textured surfaces. Such materialities should be accompanied by a similarly tactile sound in postproduction.

Show this tactile piece of jewelry through expressive bodily gestures: expose the skin, pores, and bodily fluids. If there is fabric between the jewelry and the body, delete the fabric, go straight for the skin: massage, clean, or penetrate it with the needle of a brooch.

It does not matter whether you are filming digital (e.g., AR filter; 3D-rendered piece) or physical jewelry. They trigger similar experiences when they are presented in a Hapticvisual way, incorporating glitches or other forms of visual distortion.

Using blur and other visual distortions in representing Audiovisual Jewelry can help discourage figurative language in favor of the fragmented and abstract, which in turn triggers bodily feelings in your audience.

Do not show the whole figure in the frame, only body parts. The more the parts are blurred or somehow exaggerated with video effects, the better.

Speculate on the possible bodily actions with jewelry, think of new unconventional choreography for the pieces.

Do not use small screens—the bigger, the better. Show small pieces on 4K screens to create a hyperrealistic effect. In my interviews, people have not even commented on their experiences with small screens.

Anyone can use the above advice, but the results may be less than satisfactory if you have not thoroughly considered the Metaphoric Structure of your exhibition. Remember: just because something can be done, does not mean that it should be, meaning that there is no use for jewelry that is only physical. Use big screens to produce the full effect of the Hapticvisual approach.

Upon entering the exhibition space, one experiences a transition from the world of the everyday to the world of art. The visitor should notice changes in themes, materials, emotions, associations, and poetics that signal of the oncoming of a unique Hapticvisual experience.

REFERENCES

See Laura U. Marks, The Skin of The Film, Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2000); and Laura U. Marks, Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

See Vivian Sobchack, Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004); and Vivian Sobchak, The Address of the Eye. A Phenomenology of Film Experience (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992).

Laura U. Marks, “Haptic Aesthetics,” in Oxford Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, ed. M. Kelly (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Daniel A. Serig, Visual Metaphor and the Contemporary Artist Ways of Thinking and Making (Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008).

Jonathan A. Smith, Paul Flowers, and Michael Larkin, Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2009).

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

REFERENCES

See Laura U. Marks, The Skin of The Film, Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2000); and Laura U. Marks, Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

See Vivian Sobchack, Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004); and Vivian Sobchak, The Address of the Eye. A Phenomenology of Film Experience (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992).

Laura U. Marks, “Haptic Aesthetics,” in Oxford Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, ed. M. Kelly (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Daniel A. Serig, Visual Metaphor and the Contemporary Artist Ways of Thinking and Making (Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008).

Jonathan A. Smith, Paul Flowers, and Michael Larkin, Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2009).