Conformity, cohesion and security: capturing the student body

Candice Strongwater

Text

School has meant many things to many people; it’s an institution that most have encountered, or will encounter at some point in their life. Alongside other state-sponsored establishments, schools are sites of enculturation—they are “primary agencies for shaping and reinforcing values, outlooks, beliefs, and myths that constitute citizenship in the society where they are located.”1

One type of visual evidence that I want to point to are images of the student body, which operate differently depending on the domain, medium, and genre they fall into. Captured by scholastic management, school photos circulate within a larger archipelago of educational evidence: they are a part of a “world of gates, screens, departments, papers, reports, and other media.”2

To name one example, photos taken on the ubiquitous “Picture Day” follow a relatively rote formula. The pose, the direct address, the three-fourth tilt of the head—“possibilities of subversion”3 are usually eliminated by a seamless backdrop and the instruction of the photographer. Both presences attempt to close the gaps of difference in favor of standardization. Beyond functioning as memorabilia, the ritual of picture day and the photographs themselves represent the “leveling up” from one grade to the next or the failure to do so.

Fig 1. Picture Day, Kindergarten, personal archives.

On picture day, the student sitter is aware that they are “subjects of schooling,”4 and symbolic consent is exchanged likely because there is an understanding of the image’s function. But another set of images that deserve deeper examination are those school photos tracing contemporary relations and material truths thatintersect with the darker concepts of scholastic activity and ideological interpellation: instead of images that get pinned on fridges, folded in wallets, or preserved in libraries, images captured by machines and algorithms hold the potential to end up in dangerous places—the hands of police, the homes of private third party databases, and the screens of CCTVs.

If schools are meant to be sites of knowledge production and tutelage, and help socialize the student body, what does it mean to teach, learn, and live in an environment where surveillance is a condition for “safety”? What does that say about the kinds of educational spaces we build and fund, how threat is produced and predicted, and the role of the school as a responsible actor alongside a braided network of industries with differing intentions? Whose lives are at risk of precarity?

Classroom arsenals

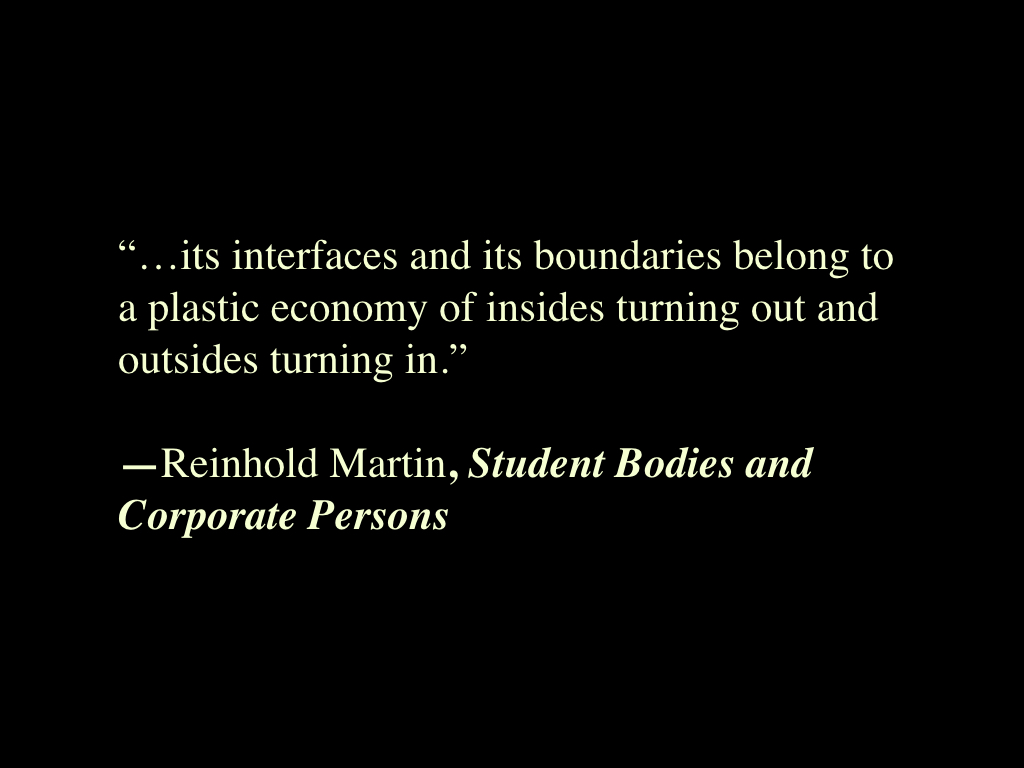

Where student portraits are to be looked at, images rendered by AI and surveillance cameras are to be used.5 Across the US, surveillance cameras are utilized in schools as a tool for monitoring the activity of student bodies. Generally speaking, they are often installed in the corners of canteens, hallways, and along the perimeter of school property, creating a totalizing environment where space can be recorded and rewound.6 The logic behind these vectors of sight is based on a kind of divide-and-conquer technique, wherein cameras are positioned at strategic locations where subjects fall under their observational gaze. Unlike the A to B compositions made by the school photographer and their subjects, security cameras multiply points of capture—and can be sutured together to complete or contest a sequence of events in question.

Fig 2. Video surveillance scheme, school floor plan.

Placed out of reach from possible interference, surveillance cameras cut through visual choke points. Specifically, the height of the camera’s installment, set between nine and thirteen feet high depending on the school’s ceiling, implies that with more optical information, more can be seen and processed. Like the seamless editing of a film, the (symbolic) violence of the apparatus’s purpose is out of sight, but not entirely concealed. As a student, to notice or acknowledge the camera is to look up, to show one’s face. But to look away might be misconstrued as a suspicious gesture. In short, the cameras’ placement is designed to catch subject(s) in a bind such that they can be seen the way the camera wants and needs its subject(s) to be visualized.

Fig 3. Picture Day, my friend Ryan, 8th grade.

Surveillance is not a new pedagogy of the State, but a belief system and practice baked into the substrate of our society. The range of its tools are used holistically across a landscape of prisons, shopping malls, museums,7 airports, big-box stores, family-owned businesses, and prosumer devices. Each of these sites holds a hidden curriculum for what is appropriate or deviant behavior. Ian G.R. Shaw notes in Predator Empire that “the individual never ceases passing from one closed environment to another.”8 A technology of enclosure, surveillance turns the world into an object to be mapped and gridded, with all its geographies and cultures cornered into something “knowable”.

In the ‘90s, schools across the country, predominantly those located in urban contexts, were already utilizing metal detectors and securitization models. But the incorporation of surveillance into US schools grew exponentially in the wake of 9/11 and the chronic episodes of school shootings that preceded and followed; schools unfortunately continue to be a site of concentrated, maddening violence. As national security protocols and public sentiment began to radically foster its concerns around gun control, terrorism, and what/how it meant to be safe, the visual presence of checkpoints, replete with armed police, full-body scanners, and weapons detection systems billed as “high-tech,” were unevenly integrated into schools that had a more diverse constituency through blue ribbon commissions and contracts. Driven by the mandate to deter “mis-behavior”9 and prevent crime and mass shootings, collective buy-ins geared schools toward acting as a new clientele. Under the banner of counterterrorism, over-policing in urban settings became a symptom that disproportionately impacted communities of color, predicting futures before life was given the chance to happen.

By the early 2010s, threat-detection techniques had an expanded repertoire. Where students once had to empty out their belongings to enter schools, checkpoints became more “efficient” through touchless security devices that were marketed as a quicker, easier, and more convenient process for screening.10 For security to work, there needs to be a consistent threat in order to legitimize its right to govern.

Fig 4. Rhombus surveillance camera promotional video.

At present, the majority of schools in NYC utilize some kind of security system, including biometric softwares, metal detectors, and AI proctoring, the latter of which was used heavily as a solution to COVID-19 related school shutdowns. As these technologies proliferate (and are projected to reach a worth of $82.9 billion by 2027), the murky extent of their consequences and harm is still unraveling.

Deep Learning

In February of 2020, The New York Times covered a story about the controversy of facial recognition technologies in US schools, reporting that the federal government released a comprehensive study finding that “most commercial facial recognition systems exhibited bias, falsely identifying African-American and Asian faces 10 to 100 times more than Caucasian faces.”11 Nora Khan, who has written extensively on ethics and tech, notes,

[...] It might ‘see’ certain people more clearly, more violently defining them, than others. And that ‘clear seeing’ is one of the most important works of cognitive capitalism. It’s not coding that is worrisome but who is writing the algorithm, whose biases are built into the code.12

In effect, using training datasets to “smarten” machine learning software are reductive and cannot process the full spectrum of identity and fluctuation. The tagging, sorting, and record-keeping of these images is done through metadata and boolean formulas—all other contingencies of the self are omitted because the organizing structure doesn’t allow for anything more than what it's asking. What’s insidious here is that judging or labeling people as appearance-based categories (skin color or gender, for instance) draws from legacies of forensic anthropometry and biological racism—histories that continue to be read through the present. Accountability varies widely across these biometric service providers, from acknowledging that bias can be transmitted digitally, to omitting these issues entirely.13

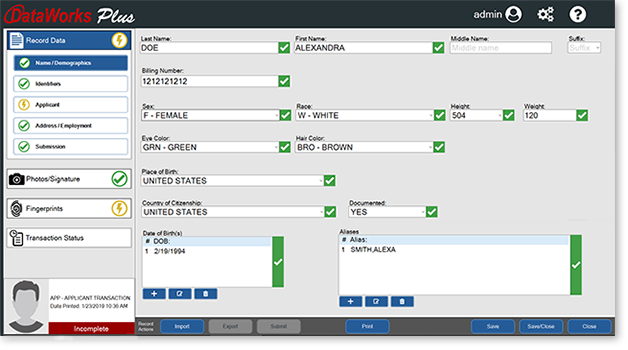

Fig 5. DataWorks database.

Another federal study showed that mistaken matches occurred at an increased rate among children. Briefly put, the camera identifies what it constitutes as a face using a learned template, then analyzes that face by measuring the distance of one’s features from each other. But the AI cannot negotiate the threshold of growing faces. When these AI systems fail to recognize a match, they use the mistake tolearn by collecting a massive volume of data and re-framing that data; these companies may consequently use children’s faces to help make the software more accurate, as many tech reform advocates fear.14 A key privacy issue at stake is that there may not be consent or transparency about how these systems and student biometrics will be used on school grounds and beyond in the long-term. Equally disquieting is that there are no federal policies in place that prevent law enforcement or immigration authorities like ICE from accessing childrens’ biometric data as part of their “surveillance dragnet.” Moreover, given that vulnerabilities and leaks in softwares are inevitable, biometric data may be hacked by a bad actor and weaponized15. This creates a snowball effect wherein data management becomes even more entangled in the securitization market, and schools must continue looking to cybersecurity companies for safeguarding.

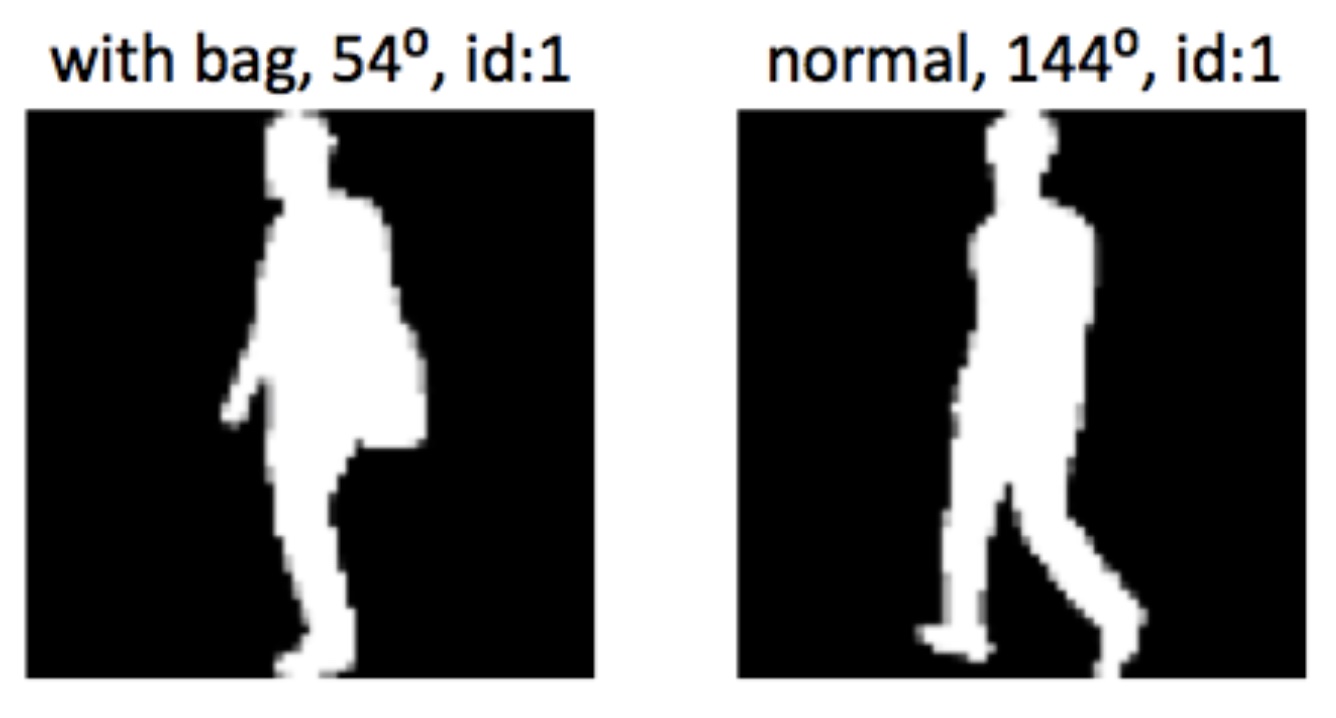

Fig 6. Gait recognition study.

Under the auspices of school surveillance—or, as one student put it, “eyes on me regardless,”16—de-contextualized gestures and encounters could be misperceived as breaking school rules, or as evidence of a crime. Combined with the reality that communities of color and communities comprised of people with lower socioeconomic status havemore police per capita in their neighborhoods/schools than wealthier or whiter areas, unequal enforcement disproportionately targets these populations who are already being overpoliced.17 Police quotas, which require cops to give out citations or make arrests at specific times, abet this practice of overcriminalization, feeding and reinforcing the school-to-prison pipeline.18

Archiving student portrait biometrics

In Lockport, NY, a recent contract between the district's law enforcement and the Lockport City School District has been under scrutiny. It acts as a useful case study in understanding the lack offederal policies and inconsistent procedures for how these new student portraits are imaged and circulated. As students enter their school, AI software compares student faces with mugshots from law enforcement databases and the school’s person of interest “Hot List,” which is set up by the school’s administrators.19 The images are then cross-checked against a private database that law enforcement uses, and if there’s a match, a notification will get sent out to school security, or result in police getting directly involved. Butbecause systemic biases and flaws are built into these algorithms, sending notifications could lead to false accusations or dangerously escalating scenarios. In a report that chronicled the status of the Lockport City School case, it was discovered that student photos and biometrics could be stored for at least three months in the law enforcement’s database; it is unclear if there are workarounds that could permit them from being able to archive the images beyond this period.20

In spite of these concerns, surveillance proponents likeJames P. O’Neill, New York City’s former police commissioner, asserted that it would be an “injustice to the people we serve if we policed our twenty-first century city without using twenty-first century technology.”21 He, like other technocrats, conveniently ignore or are oblivious to the point that race is co-produced through imaging, and that these forms of surveillance are part of a long legacy of carceral technologies that precede the twenty-first century and rely on a racializing and oppressive gaze.22

In eighteenth century New York City, candle lanterns (which became policy under the “Lantern Laws”) were required to be carried by an Indigenous, bi-racial, or enslaved Black person at night when they were in public. If we follow the logic of surveilling our society with twenty-first century technologies, then we need to acknowledge that current practices in tracking and monitoring continue a problematic and fraught lineage. In Race After Technology, Ruha Benjamin interrogates technologies that are built for efficiency, profit, and social control. She examines how the sector of high technology—from algorithms to surveillance systems—engender biased and racializing outcomes. Benjamin claims that they are designed for and synonymous with anti-Blackness, writing that “[anti-Blackness] is not only a symptom or outcome, but a precondition for the fabrication of such technologies.”23

Some cities and states have placed moratoriums on facial recognition cameras in schools (NYC’s K-12 schools are included here, for now), but not all have come to agree on its flaws and benefits. Eric Adams, NYC’s current mayor, recently stated that he intends to increase the use of AI facial recognition technology across the city, including in school zones.24 While the impulse to protect kids is understandable—if not instinctive—there are other ways to do it that don't over rely on an ecosystem of corporations, machines, and government contracts as solutions for the macroeconomic issues faced by schools and their communities.

On the one hand, surveillance systems may work in some scenarios and fail miserably in others, or even work against the state, for instance when footage from the recent Uvalde massacre exposed police incompetence and inaction. While there is an overwhelming consensus that surveillance in schools is harmful, there are also stories of students feeling safer, pointing to larger systemic issues around where the school sets parameters for student welfare. As a society, we’re tasked with trying to hold these multiple realities, histories, and truths together at the same time.

Unfinished business

Schools have garnered a reputation as being both contact zoneswhere “cultures [can] meet, clash and grapple with each other”25 and conflict zones prone to uneven resource distribution, politicization, and real violence. Different cities and countries wrestle with issues of privacy and surveillance across cultural and judicial contexts, frictions based on social location and national ideology, which shape and inform the logic of their education systems. Certain case studies raise the bar for vigilance—from instances of schools introducing wearable technologies,26 to schools that monitor how long students stay in the bathroom. In the face of these impositions, the student body (including teachers, parents, and school administrators) have been consistent emblems of what it looks like to contest power and fight for control over the kinds of schools (and societies) they want to be a part of.

In New York City, the voices, actions, and perspectives of youth-leadership groups like Students Break the Silence and YA-YA Network, as well as teacher/parent-led organizations such as the New York Collective of Radical Educators(NYCoRE) and the Movement of Rank and File Educators (MORE Caucus), among others, act as crucial counterforces to mayoral governance and technocratic dystopias. These movements are part of a history of educational justice initiatives focused on demilitarizing schooling through liberatory learning and political organizing.

As long as new forms of image capture continue to be developed and connected with industries of risk management that aim to predict futures and produce profit, educational institutions will need to exercise caution over what legacies these technologies are constitutive of. They also need to ask questions about what new images may be produced, and how will we witness them. Will we understand how to read them?

When filmmaker Harun Farocki articulated his concept of “operational images” as new forms of image-making made and read by machine vision, he framed them as “images that do not try to represent a reality but are part of a technical process.”27 Images of student portrait biometrics captured by surveillance tech and circulated through closed-door transmissions are not quite “operational” in a Farockian sense. Indeed, they are produced by AI, but they do need interpretation and human verification in order to “work.”28 These portraits of student biometrics become documents that, for a period of time (varying statutes of limitations), may be stranded between being unseen and seen. When they are made available to those in the business of the “work of watching,” they engender real material effects on the people who are captured within them.

At the beginning of this essay, I introduced vernacular photography to foreground how images hold evidentiary value. As Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer write, “school photographs do more than document the event of their production. Usually, they generate a future in which they will be looked at.”29

If we transpose this idea onto the “future observer” of student biometric data and their related images, we must ask: Is there a dead end to their circulation? Should they be preserved, destroyed, returned? What does an ethical archive, server, or even grave look like?

The answer will undoubtedly vary based on one’s positionality. But from the perspective of cultural conservation, I think we need to address what the right modes of archiving might be in order to prevent us from experiencing cultural amnesia over the consequences of privacy breaches, surround-sound surveillance, and “social noise.” We’ll need to create conditions for a wider community of autonomous and intergenerational arbiters who can make decisions disembedded from neoliberal impulses.

Hirsch, M., & Spitzer, L. (2019). School photos in liquid time: Reframing difference. University of Washington Press. p. 27.

Martin, R. (2021). Knowledge worlds media, materiality, and the making of the modern university. Columbia University Press. p. 7.

Hirsch, M., & Spitzer, L. (2014). School photos and their afterlives. Feeling Photography, 252–272. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822377313-011

Hirsch, M., & Spitzer, L. (2014). School photos and their afterlives. Feeling Photography, p. 256 https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822377313-011

Thomas Keenan distinguishes between images that are there for “looking” and “using.” See Keenan, T. (2014). Counter-forensics and photography. Grey Room, 55, 58–77. https://doi.org/10.1162/greya00141

An exception: cameras are not typically installed in classrooms, which creates a hierarchy of permissible times and zones of capture.

See Václav Chvátal’s “art gallery program.”

R., S. I. G. (2016). Predator empire: Drone warfare and full spectrum dominance. University of Minnesota Press. p. 169.

The term “mis-behavior” has cultural implications, and in this context, I think seeks to partition “unruly” bodies from docile ones.

Companies like Evolv Technology, which formed in 2013 and includes a client base of schools, entertainment venues, and places of worship, are industry leaders of this touchless security process. In their mission statement, Evolv is “dedicated to making the world a safer place by helping to protect innocent people from mass shootings, terrorist attacks and similar violent acts.” The corporation quotes a school client who was looking for “a solution that delivered optimal security while providing a welcoming, non-prison-like environment for everyone on campus.”

https://www.womenandperformance.org/ampersand/category/mindgoeswhere

Idemia’s “about” statement includes “these algorithms are rigorously designed, tested, and validated by our teams and recognized authorities to ensure accuracy, fairness, and efficiency in real-life situations. DataWorks doesn’t include acknowledgement of bias on their public-facing press materials.

https://www.nyulawreview.org/issues/volume-96-number-2/police-quotas/

https://www.nyclu.org/en/news/ny-school-using-face-surveillance-its-students

Ibid.

https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/news/s0610/how-facial-recognition-makes-you-safer

See Roth, L. (2019). Making skin visible through liberatory design. Captivating Technology, 275–307. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11sn78h.17

Benjamin, R. (2020). Race after technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity. p. 44.

A term borrowed from Mary Louise Pratt’s text, “Arts of the Contact Zone” (1991).

A bit further out from thinking of portraiture, but still a kind of capture and uniformity, is another technology getting traction abroad. Other forms of contemporary school monitoring include recent wearable AI classroom technologies that fuel in-class engagement. In 2019, a primary school in China provided headsets to individual students in order to monitor their concentration and behavior. The parents, the school, and the teachers became the recipient of the child’s data via a shared legend. These educational profiles, which tell the adults how well or how poorly the student focuses—including what kinds of answers they got wrong—become part of a communal legend that determines what could be considered social noise, and thus, modifies even the teacher or parent’s response to disciplinary measures. These wearable classroom technologies bring up questions around the motivations of software engineers and their collaborators, and what the criteria is for “good” and “bad” learning. Enhancing academic performance through data collection and surveillance become yet another appendage of a disciplinary paradigm shift to cognitive capitalism. As Yann Moulier-Boutang writes, “Knowledge is regarded as just a factor of production like any other, there to be mined and made over into all kinds of complex collective goods.” See Moulier-Boutang, Y. (2012). Cognitive Capitalism. Polity Press. p .IX.

Keenan, T. (2014). Counter-forensics and photography.

Keenan, T. (2014). Counter-forensics and photography.

Hirsch, M., & Spitzer, L. (2019). School photos in liquid time: Reframing difference. University of Washington Press. p. 12.

Hirsch, M., & Spitzer, L. (2019). School photos in liquid time: Reframing difference. University of Washington Press. p. 27.

Martin, R. (2021). Knowledge worlds media, materiality, and the making of the modern university. Columbia University Press. p. 7.

Hirsch, M., & Spitzer, L. (2014). School photos and their afterlives. Feeling Photography, 252–272. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822377313-011

Hirsch, M., & Spitzer, L. (2014). School photos and their afterlives. Feeling Photography, p. 256 https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822377313-011

Thomas Keenan distinguishes between images that are there for “looking” and “using.” See Keenan, T. (2014). Counter-forensics and photography. Grey Room, 55, 58–77. https://doi.org/10.1162/greya00141

An exception: cameras are not typically installed in classrooms, which creates a hierarchy of permissible times and zones of capture.

See Václav Chvátal’s “art gallery program.”

R., S. I. G. (2016). Predator empire: Drone warfare and full spectrum dominance. University of Minnesota Press. p. 169.

The term “mis-behavior” has cultural implications, and in this context, I think seeks to partition “unruly” bodies from docile ones.

Companies like Evolv Technology, which formed in 2013 and includes a client base of schools, entertainment venues, and places of worship, are industry leaders of this touchless security process. In their mission statement, Evolv is “dedicated to making the world a safer place by helping to protect innocent people from mass shootings, terrorist attacks and similar violent acts.” The corporation quotes a school client who was looking for “a solution that delivered optimal security while providing a welcoming, non-prison-like environment for everyone on campus.”

https://www.womenandperformance.org/ampersand/category/mindgoeswhere

Idemia’s “about” statement includes “these algorithms are rigorously designed, tested, and validated by our teams and recognized authorities to ensure accuracy, fairness, and efficiency in real-life situations. DataWorks doesn’t include acknowledgement of bias on their public-facing press materials.

https://www.nyulawreview.org/issues/volume-96-number-2/police-quotas/

https://www.nyclu.org/en/news/ny-school-using-face-surveillance-its-students

Ibid.

https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/news/s0610/how-facial-recognition-makes-you-safer

See Roth, L. (2019). Making skin visible through liberatory design. Captivating Technology, 275–307. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11sn78h.17

Benjamin, R. (2020). Race after technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity. p. 44.

A term borrowed from Mary Louise Pratt’s text, “Arts of the Contact Zone” (1991).

A bit further out from thinking of portraiture, but still a kind of capture and uniformity, is another technology getting traction abroad. Other forms of contemporary school monitoring include recent wearable AI classroom technologies that fuel in-class engagement. In 2019, a primary school in China provided headsets to individual students in order to monitor their concentration and behavior. The parents, the school, and the teachers became the recipient of the child’s data via a shared legend. These educational profiles, which tell the adults how well or how poorly the student focuses—including what kinds of answers they got wrong—become part of a communal legend that determines what could be considered social noise, and thus, modifies even the teacher or parent’s response to disciplinary measures. These wearable classroom technologies bring up questions around the motivations of software engineers and their collaborators, and what the criteria is for “good” and “bad” learning. Enhancing academic performance through data collection and surveillance become yet another appendage of a disciplinary paradigm shift to cognitive capitalism. As Yann Moulier-Boutang writes, “Knowledge is regarded as just a factor of production like any other, there to be mined and made over into all kinds of complex collective goods.” See Moulier-Boutang, Y. (2012). Cognitive Capitalism. Polity Press. p .IX.

Keenan, T. (2014). Counter-forensics and photography.

Keenan, T. (2014). Counter-forensics and photography.

Hirsch, M., & Spitzer, L. (2019). School photos in liquid time: Reframing difference. University of Washington Press. p. 12.